"Brokedown Palace" - the Grateful Dead (download here)

recorded 11 April 1972

Newcastle City Hall, Newcastle, UK

from Steppin' Out with the Grateful Dead (2002)

released by Grateful Dead Records (buy)

(file expires January 24th)

It's hard to find an excuse to publish a two-and-a-half year-old review of a show by a band I don't like very much. But I'm going to, anyway, because it involved a pleasantly bizarre excursion to Central Park, and this thing has stewed on my harddrive for way too long. At one point, it was supposed to have run in the Interboro Rock Tribune, though -- if it did -- I sure never saw a copy.

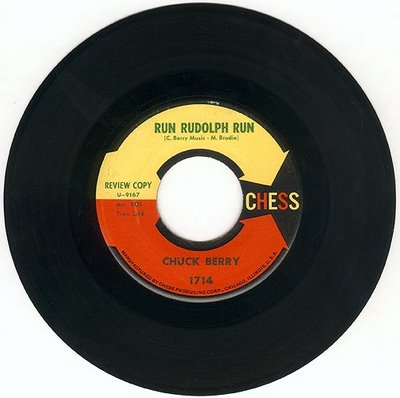

And "Brokedown Palace"? Well, why not? Consider it a spoonful of honey for all the theorizing about Dave Matthews. Or maybe it's just honey because honey is fucking delicious. Anyway, I came across this version tonight, recorded in Newcastle on April 11th, 1972, and I love it. For some reason, I can't remember ever hearing a version from '72 (or '73 or '74, my fave Dead period), though DeadBase swears there are plenty. Except for the high harmonies near the end, it's all so perfectly assured, maybe even more than the American Beauty rendition, especially Garcia's monstrously concise solo.

***

America On Line

by Jesse Jarnow

When guitarist Warren Haynes took the stage with the Dave Matthews Band during their massive free concert at Central Park on September 24th, few cheered. That was to be expected. Though Haynes is revered in some quarters as the ever-active guitarist for the Allman Brothers Band, Gov't Mule, and Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh's eponymous quintet, he's mostly unknown in the mainstream.

After dueting with Matthews on a rendition of Neil Young's "Cortez The Killer," Haynes ripped into a soaring solo. It was typical Big Rock fare, Haynes's fingers flying impassioned up the fretboard in a show of bluesy virtuosity, face scrunched in anguish and splayed across the nine jumbo screens to underscore the point. The solo blew to a volcanic climax, the tension released from Haynes's body, and he stepped back.

And, again, few cheered.

This raises some questions. Likely, it wasn't a show of displeasure. Nobody was booing, nor were people offering up any particular show of criticism. And it wasn't abject boredom. Around me, on the fringe of the crowd, people seemed to be having a grand evening under the stars, laughing and smiling in all directions. So, what was it? Why hadn't that old reliable, the Big Solo, ignited them?

On the surface, the Dave Matthews Band appear to have inherited the stadium rock mantle once held by bands like Led Zeppelin and, more recently, U2: an old-fashioned rock outfit (give or take) capable of creating best-selling records and filling impossibly large halls wherever they choose to roam. But, as the crowd's reaction to Haynes indicated, perhaps not all is what it seems.

Beneath the same ol', same ol' exterior of the rock concert as suburban coming of age ritual, the practices of young concertgoers have subtly mutated. To say that they are having shallower experiences at the shows they attend because, say, their experiences are apparently non-musical is to miss the point. They're still having a good time and they're still, like it or not, coming of age. So, what is it that they latch onto?

***

Given the truly epic surreality of the event, from its conception to is execution - light years removed from the uncomplicated cause-and-effect of liking a band, hearing about their show, buying a ticket, and going (and even further from the vaunted free concerts of yore) - it's right boggling to conceive of the AOL Concert For Schools as a teenager's first rock show. Rock concerts have always been theaters of the absurd, but the dramatis personae seem to be changing of late. In Manhattan, anyway, ads had plastered subways and buses for several weeks. Typical copy depicted a picture of a row of school desks, the AOL running man logo branded onto the corner of each (a frightening thought), and the caption "Life needs a music lesson."

Waiting on line, the acquisition of tickets seemed to be the most popular topic of discussion. Officially, they had been distributed for free via white AOL vans that parked at various Manhattan street corners throughout the week. But, being free and pretty much indiscriminately passed out - in a relatively mysterious way, at that, some seemingly arbitrarily, some after participating in contests - they quickly fell into other hands. We heard tales of a temporary black market that had sprung up to accommodate the distribution of tickets, funneling them out to the suburbs via EBay and co-workers and friends of friends with favors to call, sometimes free, but mostly not.

The line coiled through the park, a human Great Wall of China drudging in slow motion through Frederick Law Olmstead's Arcadian landscaping, disappearing into the greenery at one end, stretching out onto Central Park's bordering avenues on the other. On the east side, we had followed it south from the park's entrance at 72nd Street with no end in sight, as Jon looked for somebody to bestow his spare ticket on.

A kid overheard us. "Do you have an extra?" he asked, with a slight accent.

"Maybe," Jon replied

"Ya, I came from Germany," he said.

"Oh yeah?" I replied, glancing at his Ithaca College hoodie.

"Ya," he confirmed. "I'm from Munich."

"Okay, you got it," Jon said.

"Oh, danke!" Munich Boy grinned, and scurried off, ducking under a barricade and cutting into the line.

"Do you ever get the impression that the way these kids act on line might be a good metaphor for the way they'll turn out later in life?" I asked Jon.

He paused. "Nah, that's stupid."

We pressed onward. Near 70th Street, past a row of port-o-lets, the line suddenly changed directions, as if we had passed the equator.

"The line doubles back somewhere down there," a girl groused.

"This sucks, I wanna go home," a nearby cop grumbled. "I could be in class right now."

"Down there" was 65th Street, just north of the Central Park Zoo. "Screw this," Jon announced, and turned into the park, following the sidewalk along the thru-road. A hundred yards into the park, we hopped the small stone wall, climbed a grassy embankment, and looked down on the line, which we could see in the distance. We could see dozens of other dissidents, looking for alternate paths into the concert. I wondered how many of them were first-time concertgoers.

We cursed Munich Boy as we clamored through the underbrush after the hillside we were following suddenly dropped away. We roamed the Ramble, occasionally catching sight of the line. It was a lovely evening for a stroll, and we wandered up paths and down stairs and past the pond and the gondolas and rowboats peacefully adrift. At the Boathouse, men in white linen suits dined, seemingly unaware of the horde of teenagers milling on the other side of the treeline.

We slipped into line. "Hey, good idea, man!" a guy said, unbothered by the fact that we were blatantly cutting in.

"How long have you been here?" I asked a girl next to us.

"Five hours," she replied.

"Man, I got here three hours ago," said a kid standing next to her.

"Really?" said somebody else. "We walked up, like 45 minutes ago. Didn't even cut."

The line had broken down their sense of time, it seemed. Mine, too. I have no recollection of how long we were there. People talked. Besides how they got their tickets, they rarely spoke about the band they were there to see (unheard of at show by Phish or the Grateful Dead, two bands the DMB is frequently lumped with). They didn't even speak with particular frequency about other bands, but mostly about movies or television shows.

While this might not seem worth remarking on at first, it seems some indication of the way the Dave Matthews Band (and, thus, the rock concert as an entity) might now be viewed by young fans: music as something undifferentiated from other pop culture mediums, as opposed to an autonomous experience that exists outside of the mainstream of American life. In other words: rock not as rebellion at all, but as a completely sanctioned experience. Though this has probably been the norm for some time, the concert form has seemingly transformed around this ideal.

We passed a row of ticket takers, a pile of confiscated lawn chairs and blankets (for a day in the park, at that), a thoroughly crouch-mauling patdown (hands placed and suddenly jerked UP), and a bag search (though, officially, they weren't allowing bags in at all; terror, etc.). Though our tickets had been ripped, and word had come that the show had started, we still couldn't hear any music. Abruptly, two girls in front of us shrieked, charged up a small hill in the vague direction of the concert field, and disappeared into the woods. There was a rustling, then silence.

***

The lush green of the Great Lawn sprawled before us, the stately regency of Belvedere Castle and the midtown skyline at our back. The music ricocheted between speaker towers in an echoed maze, bearing strange sonic resemblance to an avant-garde multi-channel sound installation. Six giant screens stood in V-formation, pointing towards the distant stage, which was adorned by its own screen. Though the field was half-empty (presumably, most were still on line), clumps of people gathered around each of the screens.

Each was mounted on an elaborate scaffolding which also included several banks of lights, and a smoke machine. The former flashed constantly, moreless indiscriminately (which didn't matter, since the images were hardly synched with the music coming from the speakers). The latter, positioned below the screen, jetted smoke straight upward, thanks to industrial fans just beneath the chute. The lights and the smoke both came between one's sightline and the broadcast images, which simultaneously drew the eye in and created the impression that one was, indeed, watching something real at the center. Crowds sat cross-legged at the bases of the scaffolding, goggling upwards.

A camera mounted on a crane swept over the crowd. Another camera stood on a smaller scaffolding that rose from the midst of the throng. With the exception of a few songs in the middle of the band's set, the operator trained the camera away from the stage for the entire night, presumably for the DVD of the concert, already set to be released on November 4th. There was no shortage of striking images. A girl holding a bouquet of heart-shaped balloons of silver mylar wandered by, the balloons momentarily framed by smoke billowing from the screen.

Instead of the usual between song pandemonium, the air vacuumed to near silence after a brief smattering of applause. Despite this, the music was not an unimportant part of the event. There was dancing, though it was frequently directed at each other in clusters, like a school dance, as opposed to at the stage. There were singalongs, though only at preset moments, as opposed to when the mood struck. There were giddy screams when favorite songs were played, though they were usually followed by cell phone calls, as opposed to intent listening.

So, why is the Dave Matthews Band the premier party band of the early 21st century? Surely, part of their appeal is in their Joe Rockband quality. Matthews is, as Rolling Stone's David Fricke called him, "the ultimate Everyman." Their music maps to that description, too. Despite several long instrumental excursions, there was little extreme about the band's performance. They played at comfortable tempos with no distortion. All of this accounts for the band's accessibility, for the college following that was Matthews' bread and butter in earlier years, but doesn't explain why listeners seem to be applying different standards to Matthews' music than previous generations.

Or does it?

Despite its size, despite the screens, the show in Central Park was as close to a non-spectacle as one could get at that magnitude. When soloing, bandmembers would make a point of stepping close to each other and making eye contact. Again, it was an old rock trick (e.g. Robert Plant drawing the crowd's attention to Jimmy Page by moving near and watching him solo), but effective. But, when Plant looked at Page, he frequently did so with awe, putting the guitarist on a pedestal for the audience by temporarily playing low status.

By contrast, the Dave Matthews Band's gestures were far more humble. By design or happenstance, each revealed the band as six men playing music in real time. In an age where jump cuts are the norm and linear performances are practically unknown in popular culture, that can be powerful good. It is well possible that the Dave Matthews Band appeals for the same reason that country music suddenly found itself in vogue in the late '60s. There is not so much an authenticity to the Dave Matthews Band as there is an undiluted simplicity -- which is a helluva thing to say about a rock and roll band playing music in front of an estimated 100,000 people at a concert sponsored by one of the biggest corporations in the world.

In this case, it's not what the guitars are doing, but that there are even guitars at all. Through all, Matthews inspires a certain comfort level. And, hey, as an audience member, that feels great. It is precisely because the rock concert has become such an ingrained ritual that the Dave Matthews Band thrives: simply, at a Dave Matthews Band show, one doesn't have to behave like he's at a rock concert.

There are no pretensions of revelation, no high art or inflatable pigs, not even any obvious attempts to get the crowd riled up. Nobody was beat over the head being told that they were having the time of his or her life. Is that rebellion? Maybe so, maybe not. It's definitely a "to each his own trip" philosophy, minus the drugs and writ large. Like every Everyman, Dave Matthews is a blank slate. Life needs blank slates.

Around us, boys approached girls awkwardly, smoking the second or third cigarettes of their lives, as the new template for a rock show burned itself into their heads. They had meaningful experiences.

"This is the place to be!" a guy in a turquoise Alligator shirt bellowed as he stumbled by. "These guys are the bomb, right?"

A moment later, he held his head and staggered towards the scaffolding, where he vomited. He removed his shirt, revealing a lacrosse uniform, wiped his mouth, and lurched back into the crowd.